The History of a Crime Against the Food Law

By Harvey W. Wiley, M.D., 1929

Chapter 3: Rules and regulations

After the enactment of the food and drugs law the necessary rules and regulations for carrying it into effect were prepared. The law provided that a period of six months should elapse and that the enforcement of the law should begin on the first day of January 1907. In the preparation of these rules and regulations not only were the rights of the public at large to be conserved, but also a due regard for the ethical interests in the food and drug industries. The committee appointed to formulate these regulations held meetings in Washington, New York and Chicago. Extensive advertisements of these meetings were published and all interests involved were invited to appear and give their views.

Secretary Wilson named the Chief of the Bureau of Chemistry as his representative on the committee authorized by the law to draft the rules and regulations for the enforcement of the new act. The representative of the Treasury Department was Mr. James L. Gary; the representative of the Department of Commerce and Labor was Mr. S. N. D. North. The Chief of the Bureau of Chemistry was named chairman. My colleagues entered most enthusiastically into the discharge of the duties assigned to them. First of all they studied the act in all of its relations. We sat almost continuously every day, and always with cordial collaboration and mutual sympathy in the difficult task set before us.

On the completion of our labors we each undertook to secure the signature of our respective secretary. The Secretary of Agriculture promptly signed our report; likewise the Secretary of Commerce and Labor. Mr. Gary had some little difficulty in securing the signature of the Secretary of the Treasury. He thought that the regulations were a little bit too severe upon some of the food industries. Finally, however, he affixed his signature without any amendment whatever to the rules and regulations as presented.

During the hearings accorded interested parties there appeared before the committee practically the same interests that had been active in opposing the enactment of the law. The same arguments with which the chairman of the board had been so long familiar were repeated. Pleas for recognition of the use of borax under the regulations were made by the fishing interests of Massachusetts; the interests engaged in the manufacture of catsup begged for recognition of benzoic acid. The manufacturers of syrups pleaded for permission to use sulphur dioxide and were joined in this plea by the interests engaged in drying fruits in California.

An interesting incident occurred in this connection. It was while the committee was sitting in New York that the advocates for the recognition of sulphurous acid and sulphites were heard. A particularly earnest plea was made by the representative of the California interests, in which we were told that failure to use sulphur dioxide would ruin the dried fruit industry of that state. Reporters were constantly present at these hearings and this story of the California interests got into the afternoon papers of this city. About seven o’clock that evening the card of the California advocate was brought up to my room. When he himself appeared he was considerably embarrassed. Finally he stated the object of his visit. He said:

My wife read an account of my remarks in the afternoon papers. On my return to my apartment she chided me for what I had said. She urged me — almost commanded me — to come to see you in regard to the matter and here I am. My Wife does not allow any sulphur dioxide fruit to come onto our, own table. She is so firmly convinced of the undesirability of this kind of preservative that she will not allow me or any of my family to eat foods preserved with sulphur dioxide.

This confession on the part of the representative of the California interests I imparted to my colleagues the next morning before the hearings began.

It is hardly necessary to say that any regulation for carrying a law into effect shall not presume to ignore any function of that law. As it was provided in the law that the Bureau of Chemistry alone was to be the judge of what was an adulteration and misbranding any decision of that kind under the rules and regulations would be illegal.

The report of the committee after receiving the signature of the three cabinet officers authorized to make the rules and regulations was finally published on Oct. 17,1906.

Food Standards Committee

Quite as important as the rules and regulations for carrying out the provisions of the law was dependable information respecting the methods of judging the quality of foods and drugs by standards which were legal and conclusive in their character. About the time of the beginning of the experimental work for determining the effect of preservatives and coloring matters upon digestion was originated the idea of establishing under proper authority standards of foods. Accordingly about 1902 a section was added to the appropriation bill of the Department of Agriculture, authorizing the Secretary of Agriculture to appoint a committee of this kind. Similar action was taken by the Association of Official Agricultural Chemists. When this authority was secured the following named representatives of Agricultural Colleges and Experiment Stations were selected for this very difficult and important work: Mr. M. A. Scovell, Director of the Agricultural Station of Kentucky, Mr. H. A. Weber, Professor of Agricultural Chemistry in the College of Agriculture of the State University of Ohio, Mr. William Frear, Assistant Director of the Agricultural Experiment Station of Pennsylvania, Mr. E. H. Jenkins, Director of the Agricultural Experiment Station of Connecticut, at New Haven, and Mr. H. W. Wiley, Chief of the Bureau of Chemistry of the Department of Agriculture, at Washington, DC.

This committee was enlarged subsequently by additional members, but the five original members remained as its nucleus and principal actors until the Secretary of Agriculture at the instigation of the Solicitor of that Department abolished the committee by having the authority for its continuance withdrawn from the appropriation bill. This, however, only temporarily prevented its activities. Subsequently, after the Chief of the Bureau resigned, it was reorganized and is still at work. The value of the contribution made by these five original members is almost incalculable. We had frequent meetings lasting for days at a time, usually held at the Department of Agriculture, but in many cases we met in other cities where it was more convenient for interested parties to attend. You may have some idea of the extent of our investigations by seeing the official papers piled up on the table before us, as shown in the illustration. The results of the deliberations of this committee were published from time to time by the Department of Agriculture as official documents. They have become the guide and director, not only of the national food law, but also they have been approved and adopted by the various states.

Before this committee also appeared practically the same interests which on the enactment of the food law appeared before the committee to establish rules and regulations to carry the law into effect. They continually presented their claims for indulgences before the Food Standards Committee. The character of this opposition has already been definitely illustrated. It was not based on ethical grounds but on individual and industrial interests without relation to the welfare of the consuming public.

The result of all these preliminary investigations shows the wisdom and timeliness of their inauguration. Had it not been for these fundamental investigations the Bureau of Chemistry would have been totally unprepared to have organized the machinery which immediately went into effect January 1, 1907.

It is hardly necessary to add. that all the conferences, indulgences and collaborations with vested interests which thereafter were resorted to as a means of defeating the purpose of the law have effectively nullified the efficiency of the standards originally established.

The Secretaries of the Treasury and Commerce cannot be blamed for affixing their signatures to these documents. They assumed that these decisions were intended to carry the provisions of the law into effect. The Secretary of Agriculture stood in a different position. He knew the exact purpose of putting the decisions of the Remsen Board into effect. He boldly proclaimed that the Board was created to protect the manufacturers. Leaving his Solicitor to interpret the law, he was firmly convinced that these restrictions were legal and binding. He gave himself wholeheartedly to the effective plan of prohibiting the Bureau of Chemistry from exercising its duty to enforce the law according to its letter and spirit. The food and drugs law became a hopeless paralytic. It still breathed but its step was tottering and its hand shaky. The clot on its brain has become encysted. There is no hope that it will ever be absorbed. Only a capital operation will restore it to health.

Food Inspection Decisions

From June 30, 1906, the date the Food and Drugs Act became a law, until January 1, 1907, when it went into effect, numerous questions were propounded to the Bureau of Chemistry by interested parties respecting the scope and meaning of many of its requirements. The Bureau of Chemistry to the best of its ability interpreted, as the prospective enforcing unit, the intent of the law. Following the usual customs in such cases these opinions were taken to the Secretary of Agriculture for signature. The last Food Inspection Decision prior to 1907 was No. 48, issued Dec. 13, 1906.

For a few days after January 1, 1907, the Bureau of Chemistry was unrestricted in its first steps to carry the law into effect. Although all matters relating to adulteration or misbranding were now solely to be adjudicated by the Bureau, it was decided to continue to have these opinions, as heretofore, signed by the Secretary. The first decision under the new regime was signed by the Secretary Jan. 8, 1907. It discussed the time required to render decisions. It was prepared because many persons presenting problems were complaining of delay.

An open break in the plan of preparing decisions by the Bureau of Chemistry for the Secretary came in the case of F.I.D. 64, signed. by the Secretary March 29, 1907. The question was, What is a sardine?

The Bureau prepared a decision that only the genuine sardine prepared on the coasts of Spain, France and the Mediterranean Islands was entitled to that name. The Secretary, due to protests from the Maine packers, referred this problem to the Fish Commission of the Department of Commerce. The Fish Commission, which had no function whatever in describing what was a misbranding, made a decision diametrically opposed to that reached by the Bureau. It was as follows:

Commercially the name sardine has come to signify any small, canned clupeoid fish; and the methods of valuation are so various that it is impossible to establish any absolute standard of quality. It appears to this Department that the purposes of the Pure Food law will be carried out and the public fully protected if all sardines bear labels showing the place where produced and the nature of the ingredients used in preserving or flavoring the fish.

The Fish Commission, being in the Department of Commerce, would consider any commercial process or practice as of more importance than the plain provisions of the food law looking to the protection of the public against misbranding. The Secretary of Agriculture ignored the protest of the Bureau of Chemistry to this decision, placing a trade practice above the plain precepts of the law. The Secretary of Agriculture said:

In harmony with the opinion of the experts of the Bureau of Fisheries, the Department of Agriculture holds that the term sardine

may be applied to any small fish described above and that the name sardine

should be accompanied with the name of the country or state in which the fish are taken and prepared and with a statement of the nature of the ingredients used in preserving or flavoring the fish.

The Ambassador of France earnestly indicated to me in a personal interview his feeling that the sardine packers in France would be subjected to a ruinous competition by permitting young sprats and young herrings to be prepared according to the manner of the French sardine and thus enter into direct competition therewith. I believe also the French Ambassador voiced his objection to this decision in a diplomatic way with a protest filed with the Secretary of State. Both this protest and the plain provision of the law that the Bureau of Chemistry should decide all cases as to whether or not the articles were adulterated and mi sbranded failed to have any effect whatever on the Secretary of Agriculture. This was the second official departure of the Secretary of Agriculture from the plain provisions of the law. His whisky decision, which Secretary Bonaparte turned down, was the first.

The Board of Food and Drug Inspection

Soon after this incident the Board of Food and Drug Inspection was formed in the Secretary’s office. Theretofore the Chief of the Bureau of Chemistry had not affixed his official signature to the Food Inspection Decisions which he had prepared and the only signature these decisions carried was that of the Secretary of Agriculture. After the organization of the Board of Food and Drug Inspection the Secretary required that all the decisions of that Board submitted to him for approval should be signed by at least two members of the Board. The first decision thus signed was Food Inspection Decision No. 69. The three members of the Board affixed their signatures to this and the Secretary of Agriculture approved it on May 14, 1907.

Food and Drug Decisions Signed by the Secretaries Authorized by Law to Make Rules and Regulations

It so happened that when the decisions of this board were deemed of extraordinary importance the practice arose of having them approved, not by the Secretary of Agriculture alone, but by the three Secretaries authorized by law to make rules and regulations for the enforcement of the act. When these Secretaries therefore signed a Food Inspection Decision it became a rule and regulation. The first decision of this kind thus signed was Food Inspection Decision No. 76, concerning dyes, chemicals, and preservatives in foods.

Opinions of Experts

Some time prior to the issuance of this decision, and in fact long before there was any hint that the functions of the Bureau of Chemistry would be usurped illegally, questionnaires had been sent to three or four hundred prominent physiologists and dietitians in the United States as to their attitude in regard to the use of preservatives and coloring matters in foods. The questions propounded and the number of answers received, both negative and affirmative, are as follows:

- Are preservatives, other than the condimental preservatives, namely, sugar, salt, alcohol, vinegar, spices and wood smoke, injurious to health? Affirmative, 218; negative, 33.

- Does the introduction of any of the preservatives, which you deem injurious to health, render the foods injurious to health? Affirmative, 222; negative, 29.

- If a substance added to food is injurious to health, does it become so when a certain quantity is present only, or is it so in any quantity whatever? Affirmative, 169; negative, 79.

- If a substance is injurious to health, is there any special limit to the quantity which may be used which may be fixed by regulation of our law? Affirmative, 68; negative, 183.

- If foods can be perfectly preserved without the addition of chemical preservatives, is their addition ever advisable? Affirmative, 12; negative, 247.

It is readily seen from this tabulation that the opinion of physiologists, hygienists, health officers and physicians in the United States to whom these questionnaires were sent is overwhemingly against their use. These opinions of distinguished experts were obtained before the Remsen Board was ever thought of. (Food Inspection Decision No. 76, Pages 5 and 6.)

Food Inspection Decision No. 87 is signed by the three Secretaries as a rule and regulation. It is neither. It was an opinion that the term corn sirup

is a proper label for the substance commonly known as glucose. This opinion repealed the opinion of the Bureau of Chemistry, which, after a long argument, was endorsed also by the other two members of the Board of Food and Drug Inspection. Thus the three Secretaries authorized by law to make rules and. regulations usurped the function of the Bureau of Chemistry in regard to what was a proper label under the law.

Food Inspection Decision No. 102 was signed by the three Secretaries, legalizing the introduction into the United States of vegetables greened with copper. This was clearly another usurpation of the functions of the Bureau of Chemistry.

Food Inspection Decision No. 104 legalized the use of benzoate of soda and benzoic acid and was signed by the three Secretaries authorized by law to make rules and regulations for carrying out its purposes. It was directly contrary to the decision of the Bureau of Chemistry that these preservatives were illegal under the Act.

Food Inspection Decision No. 107 is the opinion of the Attorney-General that the Referee Board was appointed in a perfectly legal way. In making this decision Mr. Wickersham vetoed the decision of Assistant Attorney-General Fowler, holding that the Referee Board was illegally appointed. He adopted in the main the decision of Solicitor George P. McCabe that it was legally appointed. The Referee Board usurped many of the specific functions of the Bureau of Chemistry, committted to that Bureau by express wording of the Act.

Food Inspection Decision No. 113 as to the proper labeling of whisky and its mixtures, a function specifically confided to the Bureau of Chemistry by law, was signed by the three Secretaries, authorized to make rules and regulations for carrying the law into effect. It repealed the decision of the former Attorney-General, Mr. Charles J. Bonaparte, and all previous Food Inspection Decisions relating thereto.

Food Inspection Decision No, 118 is an extension of No. 113, just described, and of the same character.

Food Inspection Decision No. 127 is a decision of Attorney-General Wickersham in regard to the proper labeling of whiskies sold under distinctive names. It is also a complete reversal of the decisions in regard to proper labeling reached by the Bureau of Chemistry, and confirmed by many decisions of federal courts.

Food Inspection Decision No. 135, in regard to saccharin, is a direct assumption of authority granted specifically by law to the Bureau of Chemistry. It was signed by the three Secretaries authorized to make the rules and regulations for carrying the law into effect.

Food Inspection Decision No. 138 refers to the same subject and is signed by the three Secretaries.

Farewell to McCabe and Dunlap

On the publication of the report of the findings of the Moss Committee Mr. George P. McCabe retired from the Board of Food and Drug Inspection, and Mr. F. L. Dunlap was given an indefinite leave of absence. Mr. R. E. Doolittle was appointed in Mr. McCabe’s place.

Food Inspection Decision No. 140, issued Feb. 12, 1912, was signed by H. W. Wiley and R. E. Doolittle and approved by James Wilson.

On Feb. 17, 1912, Mr. Dunlap, having returned from his vacation, signed together with H. W. Wiley and R. E. Doolittle Food Inspection Decision No. 141.

On Feb. 29, 1912, Food Inspection Decision No. 142, in regard to the use of saccharin in foods, was signed by two of the Secretaries, namely James Wilson and Charles Nagel, but the Secretary of the Treasury dissented. This was a function specifically committed to the Bureau of Chemistry by the law.

The last Food Inspection Decision which I signed was No. 141 as to the proper labeling of maraschino cherries. Mr. R. E. Doolittle was appointed as acting chief and took my place as Chairman of the Board of Food and Drug Inspection for the remainder of its hectic career.

Mr. F. L. Dunlap resigned from his position as Associate-Chemist at the time of the inauguration of President Wilson in his first term as President. Dr. Carl L. Alsberg, who had been appointed Chief of the Bureau of Chemistry in the place of R. E. Doolittle, became by that office the Chairman of the Food Inspection Board and became associated with Dr. W. D. Bigelow and Dr. A. S. Mitchell as the new Board of Food and Drug Inspection, the first decision of which was approved by James Wilson, Secretary of Agriculture, Jan. 24, 1913.

Resignation

On March 15, 1912, having been convinced that it was useless for me to remain any longer as a Chief of the Bureau which had been deprived of practically all its authority under the law, I resigned.

Letter of Resignation of Dr. H. W. Wiley, March 15, 1912.

In retiring from this position after so many years of service it seems befitting that I should state briefly the causes which have led me to this step. Without going into detail respecting these causes, I desire to say that the fundamental one is that I believe I can find opportunity for better and more effective service to the work which is nearest my heart, namely, the pure food and drug propaganda, as a private citizen than I could any longer find in my late position.

In this action I do not intend in any way to reflect upon the position which has been taken by my superior officers in regard to the same problems. I accord to them the same right to act in accordance with their convictions which I claim for myself.

After a quarter of a century of constant discussion and effort the bill regulating interstate and foreign commerce in foods and drugs was enacted into law. Almost from the very beginning of the enforcement of this act I discovered that my point of view in regard to it was fundamentally different from that of my superiors in office. For nearly six years there has been a growing feeling in my mind that these differences were irreconcilable and I have been conscious of an official environment which has been essentially inhospitable. I saw the fundamental principles of the food and drugs act, as they appeared to me, one by one paralyzed or discredited.

It was the plain provision of the act, and was fully understood at the time of the enactment, as stated in the law itself, that the Bureau of Chemistry was to examine all samples of suspected foods and drugs to determine whether they were adulterated or misbranded and that if this examination disclosed such facts the matter was to be referred to the courts for decision. Interest after interest, engaged in what the Bureau of Chemistry found to be the manufacture of misbranded or adulterated foods and drugs, made an appeal to escape appearing in court to defend their prac tices. Various methods were employed to secure this end, many of which were successful.

One by one I found that the activities pertaining to the Bureau of Chemistry were restricted and various forms of manipulated food products were withdrawn from its consideration and referred either to other bodies not contemplated by the law or directly relieved from further control. A few of the instances of this kind are well known. Among these may be mentioned the manufacture of so-called whisky from alcohol, colors and flavors; the addition to food products of benzoic acid and its salts, of sulphurous acid and its salts, of sulphate of copper, of saccharin and of alum; the manufacture of so-called wines from pomace, chemicals and colors; the floating of oysters often in polluted waters for the purpose of making them look fatter and larger than they really are for the purposes of sale; the selling of mouldy, fermented, decomposed and misbranded grains; the offering to the people of glucose under the name of

corn sirup,thus taking a name which rightfully belongs to another product made directly from Indian corn stalks.The official toleration and validation of such practices have restricted the activities of the Bureau of Chemistry to a very narrow field. As a result of these restrictions I have been instructed to refrain from stating in any public way my own opinion regarding the effect of these substances upon health, and this restriction has interfered with my academic freedom of speech on matters relating directly to the public welfare.

These restrictions culminated in the summer of 1911 with false charges of misconduct made against me by my colleagues in the Department of Agriculture, which had it not been for the prompt interference on the part of the President of the United States (William Howard Taft), to whom I am profoundly grateful, would have led to my forcible separation from the public service. After the President of the United States and a committee of Congress, as a result of a searching investigation, had completely exonerated me from any wrong doing in this matter, I naturally expected that those who had made these false charges against me would no longer be continued in a position which would make a repetition of such an action possible. The event, however, has not sustained my expectations in this matter. I was still left to come into daily contact with men who secretly plotted my destruction.

I am now convinced that the freedom which belongs to every private American citizen can be used by me more fruitfully in rallying public opinion to the support of the cause of pure food and drugs than could the limited activity left to me in the position which I have just vacated. I propose to devote the remainder of my life, with such ability as I have at my command and with such opportunities as may arise, to the promotion of the principles of civic righteousness and industrial integrity which underlie the food and drugs act, in the hope that it may be administered in the interest of the people at large, instead of that of a comparatively few mercenary manufacturers and dealers.

This hope is heightened by my belief that a great majority of manufacturers and dealers in foods and drugs are heartily in sympathy with the views I have held, and that these views are endorsed by an overwhelming majority of the press and of the citizens of the country.

In severing my official relations with the Secretary of Agriculture I take this opportunity of thanking him for the personal kindness and regard which he has shown me during his long connection with the department.

In a supplemental statement to Secretary Wilson, Dr. Wiley says:

In transferring the management of the Bureau of Chemistry to other hands I desire to direct your attention to a few matters in which I think you will be interested.

I have always been a believer in the civil service law and have endeavored to carry out both its spirit and its letter. For this reason I have strongly opposed, except in cases of extreme necessity, the appointment of any person in the bureau not secured from the civil service register.

It is also a matter of extreme gratification to me that in the twenty-nine years which I have been chief of this bureau to my knowledge there has never been a cent wrongfully expended and no officer or employee of this bureau has ever been accused of misappropriation of public funds.

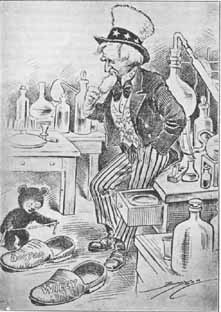

Those whose memories carry them back as far as 1912 will recall that the resignation of the Chief of the Bureau of Chemistry created quite a commotion. Not only were the newspapers and magazines full of references thereto, but the caricaturists took up the fight. One of these cartoons in the Rocky Mountain News depicted Uncle Sam bidding adieu to the departing Chief of the Bureau. Another striking cartoon depicted Uncle Sam measuring the shoes of the departed chief. Among the hundreds of editorial comments perhaps the most interesting are those made also by the Rocky Mountain News under the caption The Borgias of Business.

If the people exhibited the same persistence in looking after their interests that Illegitimate Business displays in looking after its interests, the things of which we complain would soon be brought to an end, and prosperity, like a tidal wave, would flood the land.

For twenty years at least, the food poisoners of the country have waged warfare on Dr. Harvey W. Wiley, and since the passage of the Pure Food act in 1906 they have trebled efforts to have him discharged. These Borgias of business have won, for the circumstances attending Dr. Wiley’s recent resignation make it, in practical effect, a dismissal.

Dr. Wiley resigned because the fundamental principles of the Pure Food law have been strangled; because he has been powerless to punish the manufacturers of misbranded and adulterated drugs and foods; and because the powers of his position had been nullified by executive orders. * * *

Dr. Wiley was only head of the Bureau of Chemistry, but there is every reason to believe that President Taft will find that Dr. Wiley gave the position an importance out of all proportion to its standing.